AI in Therapy: Cognitive and Clinical Impacts for Speech, Occupational, Physical, Psychomotor Therapists, and Psychologists

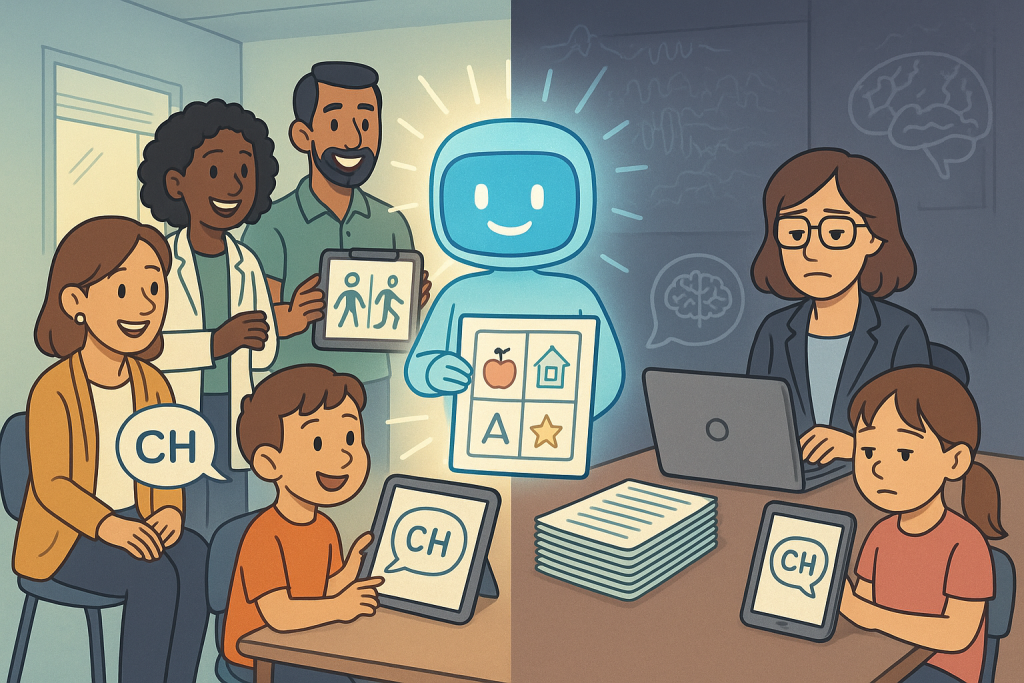

Introduction: AI’s Expanding Role in Therapy Artificial intelligence (AI), especially large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, is rapidly reshaping the landscape of healthcare and therapy. From generating therapy materials and automating documentation to providing real-time feedback and supporting client communication, AI promises greater efficiency, personalization, and accessibility for practitioners across speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, psychology, and psychomotor therapy. However, as AI becomes more embedded in daily practice, emerging research urges therapists to consider not just the practical benefits, but also the cognitive and clinical implications for both therapists and clients (Kosmyna et al., 2024). Cognitive Engagement: What Happens When We Use AI? Recent experimental research has shown that the way therapists and clients interact with AI tools can significantly affect cognitive engagement and learning outcomes. In a study by Kosmyna et al. (2024), participants were assigned to write essays using either only their own knowledge, a traditional search engine, or an LLM like ChatGPT. EEG brain activity was measured, and participants were interviewed about memory, ownership, and satisfaction with their work. The findings reveal that those who relied on LLMs exhibited the weakest neural connectivity, particularly in brain regions involved in memory, attention, and deep processing. By contrast, participants who used only their own brains demonstrated the strongest, most widespread brain activity, while those using search engines were intermediate. This suggests that LLMs, while effective at reducing immediate cognitive load and making tasks feel easier, may also encourage more passive engagement and less deep processing of information (Kosmyna et al., 2024; Sweller, 2011). Moreover, LLM users reported lower ownership over their work and struggled to recall or quote from their essays, compared to those who used search engines or worked unaided. This impaired memory and reduced sense of authorship may have important implications for therapy, where engagement, self-reflection, and memory are central to progress and learning (Kosmyna et al., 2024). Clinical Implications for Therapy Disciplines For Speech and Language Therapists:AI can generate prompts, exercises, and language models for clients, but over-reliance on these tools may reduce clients’ active participation and expressive language development. The process of generating one’s own ideas and sentences is crucial for language acquisition and memory formation (Kosmyna et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). For Occupational and Physical Therapists:AI is increasingly used in physical therapy for movement analysis, remote monitoring, and personalized exercise planning. Wearable sensors and AI-driven platforms can track gait, range of motion, and exercise adherence, providing real-time feedback and automating progress documentation. However, optimal motor learning and transfer to daily life require clients to be actively involved in planning, reflection, and problem-solving. Passive following of AI-generated routines may not engage the cognitive and motor systems as robustly as therapist-guided or self-directed activities (Sweller, 2011). For example, a PT might use AI to suggest a progression of exercises, but the best outcomes occur when clients set goals, reflect on their progress, and adapt routines in collaboration with their therapist. For Psychologists and Psychomotor Therapists:AI tools can assist with psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral interventions, and emotional support. However, therapists must be vigilant about “cognitive offloading”—the tendency to let AI do the thinking, which can diminish clients’ critical thinking, emotional processing, and self-reflection (Kosmyna et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). For All Disciplines:AI-generated documentation and treatment plans can save time, but therapists may feel less connected to these records and may struggle to recall details later. This can impact continuity of care, clinical judgment, and professional satisfaction. Furthermore, the homogenization of AI-generated content risks undermining the creativity and individualized care that are hallmarks of effective therapy (Kosmyna et al., 2024; Niloy et al., 2024). Balancing Benefits and Cognitive Risks AI tools offer clear advantages: they reduce extraneous cognitive load, streamline information retrieval, and can increase productivity (Kosmyna et al., 2024; Sweller, 2011). For PTs, this means more efficient data collection, progress tracking, and even predictive analytics for injury risk or recovery. However, these benefits come with trade-offs. Lower cognitive effort may lead to less deep engagement, weaker memory encoding, and reduced development of problem-solving skills. Studies in educational settings have found that students using AI for writing or programming tasks perform worse on measures of long-term learning, self-efficacy, and creative thinking compared to those using traditional methods (Yang et al., 2024; Niloy et al., 2024). Moreover, the tendency for AI-generated outputs to be more similar to each other—less diverse in language and thought—may limit the range of perspectives and approaches explored in therapy. This is especially concerning in fields that value creativity, individualized care, and holistic understanding of clients (Kosmyna et al., 2024). Practical Recommendations for Therapists Conclusion: Navigating the AI Era in Therapy AI is a powerful tool for therapists, including PTs, but it is not a replacement for the human mind or the therapeutic relationship. The latest research demonstrates that while AI can make tasks easier and more efficient, it may also reduce cognitive engagement, memory, and creativity if overused or used uncritically. Therapists across all disciplines must strive for a thoughtful balance—leveraging AI’s strengths while actively protecting the cognitive, creative, and relational skills that define effective therapy. By doing so, both therapists and clients can continue to grow, learn, and thrive in an increasingly AI-augmented world. References Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y. T., Situ, J., Liao, X.-H., Beresnitzky, A. V., Braunstein, I., & Maes, P. (2024). Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task. MIT Media Lab. Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive Load Theory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 55, 37-76. Yang, S., Li, J., & Chen, X. (2024). The Impact of ChatGPT on Student Learning: Evidence from a Programming Course. Computers & Education, 205, 104889. Niloy, S., Rahman, M., & Sultana, S. (2024). Effects of ChatGPT on Creative Writing Skills among College Students. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 17(1), 15-28.